2022

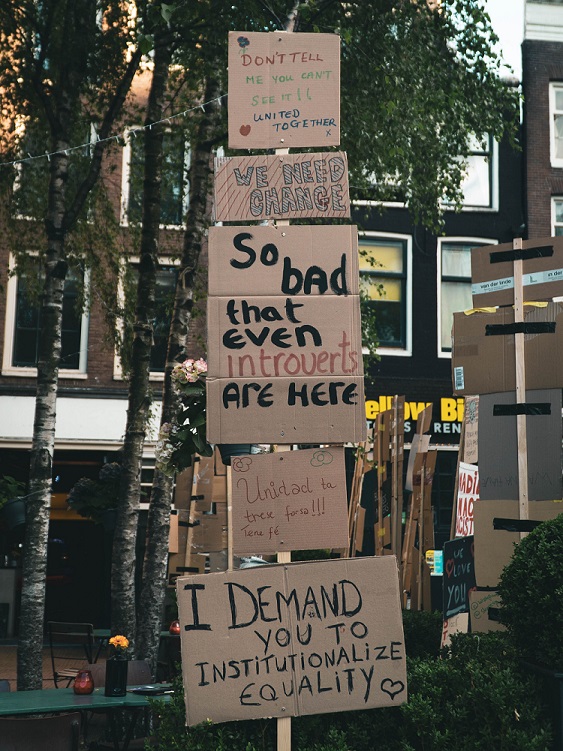

Photo by: Markus Spiske (Unsplash)

The pandemic’s disproportionate impact on women is derailing decades of progress on gender equality

During the global COVID-19 pandemic, women have carried much of the unpaid emotional and domestic burden of caring for their families and communities, often simultaneously holding down paid jobs, many on reduced hours or salaries.

Women have also been disproportionately affected by job losses, particularly women of color and ethnic minorities. Worldwide, women lost more than 64 million jobs in 2020 alone, resulting in an estimated US$800 billion loss of income.

Mirroring these trends, women in Aotearoa New Zealand faced greater economic, social and health challenges than men. In 2020, women made up 90% of pandemic-related redundancies. In 2021, many more women were working in “precarious” jobs. W?hine M?ori and Pacific women, already facing greater inequalities, have been even harder hit by job losses.

During this time, rates of domestic violence against women and girls surged in New Zealand and around the world, prompting some to refer to a “double pandemic” or “shadow pandemic”. Women’s physical and mental health has been heavily affected for both frontline workers and in the home.

As ongoing research by a cross-cultural team of feminist scholars has been documenting, New Zealand women have found different ways to cope through the various stages of the pandemic. But with the pandemic exacerbating gender inequalities in most areas of life, the fear is that decades of (albeit uneven) momentum towards gender equity is being lost.

Recovery designed for women

While some governments have taken steps to address women’s well-being during the pandemic, such as introducing shorter or flexible work hours, they remain the minority.

Organisations such as the United Nations and the OECD have identified the need to develop better support for women within pandemic recovery programmes. And some countries have advocated more progressive strategies, including prioritising local feminist and Indigenous knowledge. But the uptake of such initiatives has been minimal at best.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the 2021 Wellbeing Budget sought to “support into employment those most affected by COVID-19, including women”. But the focus on male-dominated industries (such as construction and roading), and lack of initiatives aimed at women as primary carers, meant this was largely a missed opportunity.

While this general lack of gender-responsive policy has been troubling, women have been far from passive in their own responses, both individually and collectively.

As the stories of women from diverse backgrounds in Aotearoa New Zealand have shown in our own and others’ research, many have turned to their own cultures, social networks and religions to help them through the pandemic. Others have used sport and exercise, nature and digital technology to build a sense of belonging and support during difficult times

Such strategies have helped them manage unprecedented levels of stress in their own lives, and the lives of those around them. Women have been active and creative in the ways they’ve found to care for themselves and others.

Yet these everyday acts of care by women for their families and communities are rarely seen, valued or acknowledged.

Questioning roles and expectations

As the pandemic continues, women everywhere are suffering the “hidden costs of caregiving”. In Aotearoa New Zealand, as elsewhere, new COVID variants have seen them even busier caring for sick family members – often while unwell themselves.

The effect has been to rethink priorities, who and what is most important, and to question the expectations shaping their lives.

Some of the women in our studies have taken bold steps – starting a new business, moving town, reorganising work-life balance, putting their own health first. Others have simply acknowledged their own vulnerability and need for community. As two of the women we interviewed said:

I think for me it’s been more of a reaffirmation that what I am doing is good enough […] Like I don’t need to be all of these things. We put so much pressure on ourselves […] we spread ourselves too thin […] trying to be a whole bunch of other people’s ideas of being the best person.

You need to be real about how you are feeling and a little bit vulnerable, not hide things or bottle things up or try to be everything to everybody. I learned the power of being vulnerable, of people and community, and the importance of connection and the importance of kindness and being okay with whatever you’ve got in your mind.

Learning from women’s experiences

The stress and mounting fatigue characteristic of life during COVID-19 are undoubtedly prompting many women in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas to ask questions about the gendered economic and social systems that may no longer be working for them, and the infrastructures that are failing to support them.

Some are turning away from their busy working lives, opting instead to find a slower pace, to live more sustainably, and to give back to their communities in a range of ways.

Some even refer to the gendered effects of the pandemic economy as the “great she-cession”. But it’s clear we need to better understand the social, economic and cultural conditions prompting these changes.

What we can say, however, is that genuinely gender-responsive policies are urgently needed. The often used mantra of “building back better” must prioritise the knowledge of local women in all their diversity, and there is much we can learn by listening to women’s everyday experiences of the pandemic.

Not doing so risks decades of gender equity work slipping away.

By : Holly Thorpe (Professor in Sociology of Sport and Physical Culture, University of Waikato)

Allison Jeffrey (Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Alberta)

Simone Fullagar (Professor, Gender Equity in Sport, Griffith University)

Date : April 21, 2022

Source: The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/the-pandemics-disproportionate-impact-on-women-is-derailing-decades-of-progress-on-gender-equality-180941

The fight for gender equality

Celebrating Women’s History Month, here are seven battles sportswomen have been fighting, against gender-based discrimination in sport.

The inherent masculine nature of sport often makes gender-based discrimination a common feature in it. Women’s participation in sports was restricted for a long time, and even today, women face multiple barriers to participation. Indeed, women are still struggling to compete on an equal playing field.

Nevertheless, women in sport have been persistent in questioning the gender-based disparities and inequalities. Here are some of the battles that women in sport have been fighting, to challenge the sexism within sport.

The fight for equal pay

Dipika Pallikal, one of India’s top-ranked squash players, refused to compete in four consecutive national championships, starting in 2012, due to the pay disparity between male and female players. Pallikal made a comeback only after prize money was equalised by the organisers of the championship. She received flak from many for abandoning the championship for four years, as it was not seen in sync with the ‘sportsmanship spirit’. The criticism did not stop Pallikal from demanding equal pay and she was successful in bringing change for women in squash.

Many other sportswomen around the world have been lobbying for equal pay. The recent landmark settlement between the US National Women’s Soccer Team, against the US Soccer Federation, is a historic win for women’s sport and will pave the way for many other women demanding their right to equal pay.

The fight for maternity benefits

Maternity benefits are rarely provided to female athletes. This causes them to lose out on sponsorship and brand deals, often shortening their careers. The lack of maternity leave policies in sport federations has forced many sportswomen to choose between their careers and motherhood.

In January 2022, after negotiating new contracts, women footballers across 24 clubs in England were granted maternity benefits. This move, which was approved by the Professional Football Association (PFA), is an example of sportswomen negotiating equal labour rights in their professions.

This move is part of a growing wave of sportswomen negotiating maternity benefits for themselves and other female athletes. In 2020, the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) announced a new collective bargaining agreement, which increased salaries and provided fully paid maternity leave. In the same year, FIFA also approved a 14-week maternity leave for all players and declared that all football clubs would be obligated to integrate the players after their pregnancy.

The fight against gender testing

Sport federations often use sex testing as a tool to control which women can participate; using questionable scientific evidence as their basis, federations claim that high levels of testosterone give some women a competitive advantage. This is a highly contested claim which excludes some women from participating, often leaving them with no choice but to suppress their naturally occurring hormones, which can have a long-term impact on their bodies. Further, these rules have often been used disproportionately against women of colour, limiting their access to competitive sport.

Caster Semanya, a two-time Olympic gold medalist from South Africa, has been fighting a battle against World Athletics since 2019. In 2018, World Athletics banned Semanya from competing in races between 400 and 1600 metres, due to her naturally high levels of testosterone. They ruled that she could only participate if she medically suppresses her testosterone or undergoes surgery.

Since then, Semanya has legally challenged World Athletics’ discriminatory rules in three different courts. Though she has lost the appeals made to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and Switzerland’s Federal Supreme Court in 2019 and 2020, she has not given up her fight. In February 2021, she took her case to the European Court of Human Rights. Despite her persistent efforts, Semanya was not allowed to participate in the 800 metre race at the Tokyo Olympics held in 2021.

Semenya is not alone in this battle. Dutee Chand, who has also faced the brunt of these rules, has been supportive of Semenya and Olympic champion and American gymnast Simone Biles has also been a vocal supporter. However, Semenya has commented on the lack of support from other female athletes and how she has had to often deal with rude comments from her competitors.

The fight for participation

When Bobbi Gibb decided to run the Boston Marathon in 1966, it was an all-male event, with women not allowed to participate. Indeed, at the time, women were not allowed to participate in any running events over 1.5 miles, due to the misperception that women were not physically able to run long distances. Despite being denied entry to the marathon, Gibb did not give up - she hid in the bushes and disguised herself, as she mustered the courage to break the rules and complete the marathon, stunning and impressing the audience. She was eventually disqualified from the race because she was a woman.

A year later, in 1967, Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to officially participate in the Boston Marathon - in her registration form, she signed using her initials, and it was not apparent that she was a woman. However, the race co-director Jack Semple, was furious at her participation, and he disrupted the race as he attempted to remove her bib. Unperturbed, she persevered and completed the race.

It still took five more years for the Boston Marathon to officially allow women to participate in the event - in 1972, eight women participated in the Marathon, and Nina Kuscsik became the first female champion of the event. By 2015, the number of female participants at the Boston Marathon had grown to 14,000.

Gibb and Switzer were pioneers for women’s participation in long distance running. Switzer also played a pivotal role in getting the women’s marathon into the Olympic Games, and the first-ever women’s marathon at the Olympics was held at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

The fight against gender roles

Hassiba Boulmerka is a former athlete from Algeria, who became a role-model for many female athletes in Africa. She began to run at the age of 10, later specialising in the 800 and 1500 metre races. Her breakthrough achievement came in 1991, when she became the first African woman to have won a World Athletics title.

Her journey, however, was not easy. Boulmerka was often targeted by radical religious groups for showing too much skin while competing. Due to the constant threats she received, including threats to her life, she was forced to move to Berlin in 1992. In defiance of these threats, she continued to run, and won a gold medal at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Boulmerka’s fearless battle against restrictive gender norms and stereotypes was a step forward for women in sports, especially African women.

The fight against mandated uniforms

During the 2021 European Beach Handball Championship held in Bulgaria, the Norwegian Women’s Beach Handball Team protested against the uniform mandated by the European Handball Federation. The team wore shorts, as opposed to bikini bottoms, the uniform fixed by the federation. The team’s refusal to abide by the clothing rules was not received well by the federation, and they were fined $1500 for the offence. However, the Norwegian Handball Federation backed the team and supported their stance on the mandated dress code.

It has been a long fight against mandated uniforms for women in sport, which are often rooted in sexism. Often, uniforms can be a reason which limits the participation of women and girls in sports. This is why it is important for sports federations and organisations to ensure that all women and girls are able to participate and compete in sport in those clothes which make them feel comfortable.

In this fight against mandated uniforms, it is important to recognise those women that have fought for their right to wear the hijab while participating in sports. The gains made in this battle are recent - in 2016, Ibtihaj Muhammad was the first American Muslim to compete at an Olympics while wearing a hijab, and the FIFA ban against headscarves was only lifted in 20143.

Women are starting to take control of the narratives on their bodies and comfort. These recent wins are indicative of a growing movement towards increasing women’s comfort (and hence participation) in sport.

The fight against sexual harassment

In November 2021, Peng Shui, a Chinese tennis player, accused China’s former vice-sexually harassing her. The Chinese media, however, suppressed the news and Shui disappeared from public view soon after sharing her story. Shui is considered a pioneer in women’s sport for speaking out against sexual harassment, especially against a powerful man.

Shui is not alone in this fight against sexual harassment. Perhaps one of the most visible cases of sexual harassment against female athletes came in 2016, when over 250 American female gymnasts, including Olympians McKayla Maroney and Simone Biles, accused US Gymanstics’ doctor Larry Nasser of sexually abusing them.

For sport to be a safe space for women, it is important that strict measures are taken against sexual harassment, to ensure that they are protected. Without such safeguarding, women will not be able to participate in sport freely.

The battles ahead

These are only a few of the battles against gender-based inequalities that female athletes have had to fight. Though there have been significant moves towards equality, many battles lie ahead.

This is also not an exhaustive list of all the brave sportswomen who have been fighting for equality. In this long journey towards gender-based equality, no small group of women are responsible for the changes that we have witnessed - indeed, the wins are the culmination of the hard work of many changemakers who have challenged misogyny in sports. And today, with many more female athletes speaking up against discrmination and for gender equality, the tides are certainly changing in sport.

By : Isha Saxena & Tariqa Tandon

Date : March 22, 2022

Source: sportanddev.org

https://www.sportanddev.org/en/article/news/fight-gender-equality

Does gender matter? The association between different digital media activities and adolescent well-being

Abstract

Background

Previous research on the relationship between social media use and well-being in adolescents has yielded inconsistent results. We addressed this issue by examining the association between various digital media activities, including a new and differentiated measure of social media use, and well-being (internalizing symptoms) in adolescent boys and girls.

Method

The sample was drawn from the four cross-sectional surveys from the Öckerö project (2016–2019) in eight municipalities in southern Sweden, consisting of 3957 adolescents in year 7 of compulsory education, aged 12–13. We measured the following digital media activities: playing games and three different activities of social media use (chatting, online sociability, and self-presentation). Our outcome measure was internalizing symptoms. Hypotheses were tested with linear regression analysis.

Results

Social media use and playing games were positively associated with internalizing symptoms. The effect of social media use was conditional on gender, indicating that social media use was only associated with internalizing symptoms for girls. Of the social media activities, only chatting and self-presentation (posting information about themselves) were positively associated with internalizing symptoms. Self-presentation was associated with internalizing symptoms only for girls.

Conclusion

Our study shows the importance of research going beyond studying the time spent on social media to examine how different kinds of social media activities are associated with well-being. Consistent with research in psychology, our results suggest that young girls posting information about themselves (i.e. self-presentation) might be especially vulnerable to display internalizing symptoms.

By : Robert Svensson, Björn Johnson & Andreas Olsson

Date: February 10, 2022

Source: BMC Public Health

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-12670-7

Svensson, R., Johnson, B. & Olsson, A. Does gender matter? The association between different digital media activities and adolescent well-being. BMC Public Health 22, 273 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12670-7

Without data, Indonesia's gender equality promise falters

Missing gender data means Indonesia's development programmes are poorly targeted, hindering gender mainstreaming goals enacted 22 years ago.

Indonesia, a strongly patriarchal society, is trying to close the gender gap. Progress has been slow.

Indonesia’s gender inequality index is among the highest of the ASEAN countries, according to the United Nations. Only Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar rank lower. Indonesia is 85th out of 149 countries in the global gender gap rankings.

Despite having the same level of education, Indonesian women and men still experience significant wage differences, with women earning 59.3 percent of what their male counterparts with the same level of schooling bring home.

Many Indonesian women choose jobs related to domestic work as caregivers, nurses, and teachers. They also tend to work in the informal sector, missing out on the empowerment that formal work offers. The wage gap is not just large in rural areas. Data for urban areas shows the average salary of female workers is IDR2,722,531 (US$190), while men get an average wage of IDR 3,503,050 (US$244).

Indonesia’s government is not ignoring the issue — it ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women some 22 years ago. However, it lacks the gender-differentiated data and information to thoroughly assess the situation and develop appropriate, evidence-based responses and policies.

Indonesia has adopted the idea of gender mainstreaming — bringing gender perspectives and the goal of gender equality to all activities — policy development, research, advocacy, dialogue, legislation, resource allocation, as well as the planning, implementation and monitoring of programmes and projects. But the promise is not reflected in government budgeting.

Despite a strategy launched in 2013 to adopt gender-responsive budgeting, Indonesia does not state exact figures regarding the nominal financing for gender-responsive programs. It could learn from the Philippines. Its government requires all national agencies to set aside 5 percent of their allocation of funds for gender and development. In 1998, this was expanded so that both local and national government agencies could develop gender-responsive planning and budgeting capabilities.

Indonesia’s progress toward gender equality also remains slow because gender mainstreaming is largely just aligned with governments or institutions focused on women’s empowerment affairs. This simply reinforces the outdated understanding that gender issues are not mainstream and do not cut across all sectors.

There is also a lack of skilled people in government with an understanding of gender issues and the need for gender-disaggregated data.

Ideally, several years’ of data would be available for policymakers to allow them to track changes and take corrective action. In reality a lack of sex-disaggregated data has resulted in an incomplete picture of women’s and men’s lives — and the gaps that persist between them.

Globally, close to 80 percent of countries regularly produce sex-disaggregated statistics on mortality, labor force participation, and education and training. But less than one-third of countries disaggregate statistics by sex on informal employment, entrepreneurship (ownership and management of a firm or business) and unpaid work, or collect data about violence against women.

More and better data is required to contribute to a meaningful policy dialogue on gender equality and provide a solid evidence base for development policy. Disaggregated data can be hard to come by in some regions of Indonesia. Data is available only in certain fields that are relatively easy to measure such as education, health and employment.

As an example of data on the poor, some data sources list the number of poor women and men, but give no clear age division. But poverty impacts children, adults and the elderly in different ways. As a result, many programmes are not well targeted because they do not take into account the needs of the different recipients of poverty reduction programs.

Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency is responsible for disaggregated data, most of which is quantitative and general in nature. Getting specific and qualitative data is costly.

This unintegrated data collection is a problem for many institutions, considering not all government institutions in the regions have a budget for data collection.

The best hope for change is in the realm of Indonesia’s development planning. Gender equality can contribute to economic growth, and programmes making it into Indonesia’s development planning are assigned funding. Scrutiny of gender-responsive programs within this envelope could help improve planning and funding in future budgets.

Antik Bintari is a researcher and lecturer at the Gender and Children Research Centre at Indonesia’s Universitas Padjadjaran. Her works focuses on politics, governance, gender and child issues.

By : Antik Bintari

Date: March 7, 2022

Source: eco-business.com

https://www.eco-business.com/opinion/without-data-indonesias-gender-equality-promise-falters/

Differences in the spatial landscape of urban mobility: Gender and socioeconomic perspectives

Abstract

Many of our routines and activities are linked to our ability to move; be it commuting to work, shopping for groceries, or meeting friends. Yet, factors that limit the individuals’ ability to fully realise their mobility needs will ultimately affect the opportunities they can have access to (e.g. cultural activities, professional interactions). One important aspect frequently overlooked in human mobility studies is how gender-centred issues can amplify other sources of mobility disadvantages (e.g. socioeconomic inequalities), unevenly affecting the pool of opportunities men and women have access to. In this work, we leverage on a combination of computational, statistical, and information-theoretical approaches to investigate the existence of systematic discrepancies in the mobility diversity (i.e. the diversity of travel destinations) of (1) men and women from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and (2) work and non-work travels. Our analysis is based on datasets containing multiple instances of large-scale, official, travel surveys carried out in three major metropolitan areas in South America: Medellín and Bogotá in Colombia, and São Paulo in Brazil. Our results indicate the presence of general discrepancies in the urban mobility diversities related to the gender and socioeconomic characteristics of the individuals. Lastly, this paper sheds new light on the possible origins of gender-level human mobility inequalities, contributing to the general understanding of disaggregated patterns in human mobility.

By : Mariana Macedo, Laura Lotero, Alessio Cardillo, Ronaldo Menezes &Hugo Barbosa

Date: March 2, 2022

Source: PLOS ONE

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0260874

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260874

Photo by: Sten Rademaker (Unsplash)

Putin puts international justice on trial – betting that the age of impunity will continue

Images of pregnant women fleeing a bombed maternity ward in Mariupol, Ukraine, raised again the question of how far the Russian military will be willing to go to conquer the country – and whether war crimes are being committed.

In just over two weeks of the invasion, the World Health Organization has verified 39 attacks by Russians on health care facilities. Ukraine claims more civilians than Ukrainian soldiers have already been killed.

International humanitarian law, constituting agreements between countries on the laws of conduct in war, requires militaries to avoid the deliberate targeting of civilians and the use of weapons like cluster munitions that are indiscriminate – in other words, have a high chance of affecting civilians.

It also calls on warring nations to prevent extensive damage to civilian infrastructure, such as schools, residential buildings and hospitals. Simply stated, under these criteria, war crimes take place when there is excessive destruction, suffering and civilian casualties. Rape, torture, forced displacement and other actions may also constitute war crimes.

There are other international crimes, including genocide and crimes against humanity. The latter consists of similar acts like rape and murder undertaken as part of widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.

As a scholar of human rights and the law, I believe there is clear evidence that Russia has already engaged in violations of international law, including war crimes. Although the potential for holding Russian commanders, and even President Vladimir Putin, accountable and punishing them for international crimes is more likely than in the past, the path is likely long and difficult. Moreover, it is unknown what effect, if any, the specter of prosecution will have on the course of the war.

That’s because international justice has been unable to either prevent or prosecute many perpetrators of war crimes in the past decade.

History repeating

International law experts point to the earlier ravages of Russian military actions in both Chechnya and Syria as an indicator of the tactics Putin is willing to use in the invasion of Ukraine.

Russia fought two wars against the breakaway republic of Chechnya in the years following the fall of the Soviet Union. The second – in which Putin cut his teeth as a wartime leader – was seen as particularly brutal.

During that 1999-2000 conflict, advocacy group Human Rights Watch collected evidence that Russia carpet-bombed the capital Grozny and other towns, causing heavy civilian casualties – estimates run into the tens of thousands killed – and leaving much of the capital destroyed.

There is also compelling evidence that war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed during Russia’s occupation of South Ossetia in Georgia in 2008 and in relation to its annexation of Crimea and engagement in eastern Donbas region in Ukraine in 2014.

In 2015, Russia participated in Syria’s civil war on the side of President Bashar al-Assad by providing Russian air support to Syria’s army. According to Human Rights Watch, the aerial bombardment of Aleppo supported by the Russians in 2016 was “recklessly indiscriminate, deliberately targeted at least one medical facility, and included the use of indiscriminate weapons such as cluster munitions and incendiary weapons.”

The United Nations concluded that the Russian air force was responsible for war crimes in the Syrian province of Idlib in 2019, having bombed indiscriminately a major marketplace and a displaced persons camp, killing and injuring scores of men, women and children. Russian denied any culpability. And no charges against Putin or Russian military commanders have ever been formally pursued internationally for alleged crimes in Chechnya or Syria.

The United States recently raised the prospect of Russia’s deploying prohibited chemical weapons in Ukraine. If it does so, it will be following the lead of Putin ally Assad, whose government is known for its use of prohibited chemical weapons against civilians in Syria.

Either way, military experts expect Russia’s tactics in Ukraine to only intensify in its brutality and disregard for the laws of war.

In search of accountability

Many scholars pin their hopes for accountability on the International Criminal Court, which was established under the Rome Statute in 1998 with 123 states parties. The aim of the court is to prosecute those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and aggression.

Although neither Russia nor Ukraine is a party to the Rome Statute, the ICC has initiated an investigation into alleged crimes based on a special declaration by Ukraine. This gives the ICC legal authority to investigate and prosecute alleged crimes committed in Ukraine since 2014.

But while this early action means that evidence might be collected in real time and speed up the usually slow process of international justice, there are still substantial problems in prosecuting these alleged crimes.

The standards set for proving massive and complex international crimes are more daunting than for domestic crimes. It is even harder to prove command responsibility by a head of state, such as Putin, particularly when there is no cooperation between the ICC and the country of the accused. Successful cases are few and have taken place only after a leader’s fall from power and only if the court has cooperation with the country. That’s how Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia was prosecuted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Similarly, former President Charles Taylor of Liberia was prosecuted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone.

Other options for criminal trials exist outside the ICC but also face major obstacles. Advocates have harnessed the concept of universal jurisdiction – inspired by the efforts of Spain to bring former dictator Augusto Pinochet of Chile to justice – to bring perpetrators of war crimes in Syria to trial in European courts.

Legal experts are also looking at the prosecution of Putin and Russian leadership directly for the crime of aggression in regards to Ukraine.

For this crime, the ICC does not have legal authority to prosecute Putin without a U.N. Security Council referral. Given that Russia has a seat on the Security Council, where it wields a veto, that won’t happen. Options include establishing a special tribunal by Ukraine with U.N. General Assembly endorsement or other international support.

But the ICC and special courts are “made from scratch” institutions, with limited capacity and without a police force. Practically, getting Putin or other Russian leaders into any court is an issue. For example, the ICC still struggles to capture former Sudan President Omar al-Bashir, accused of genocide and other crimes in Darfur, despite issuing arrest warrants for him in 2009 and 2010.

Age of impunity

Advocates point out that impunity – the ability to escape responsibility for violations of international law – has been on the rise for many years, along with authoritarianism.

That means the initiation of criminal investigations might have little impact on the calculations of Putin, senior Russian leadership or commanders and soldiers on the ground in Ukraine. Some international law experts argue that even where actual prosecution and punishment might not be immediate, actors who care about their legitimacy domestically or internationally are more likely to be deterred from committing more crimes by potential prosecutions. However, there are no firm conclusions about the preventive or deterrent effect of international justice.

The actions of Russia in Ukraine might spur investigations at an unprecedented pace. And the ICC can issue arrest warrants in order to prevent the further commission of crimes. Such warrants would affect the accused’s ability to travel and officially represent the country.

When, or if, the formal label of accused “war criminal” gets attached to specific Russian names, it is possible that the prospect of accountability will become a more significant factor in the decision-making of those responsible for the ruthless war in Ukraine. But it will still be too late for the many victims already being identified.

By : Shelley Inglis (Executive Director, University of Dayton Human Rights Center, University of Dayton)

Date: March 15, 2022

Source: The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/putin-puts-international-justice-on-trial-betting-that-the-age-of-impunity-will-continue-178836

Addressing gender inequalities in research through institutional change

Gender equality and inclusion are key metrics by which performance is measured in industry today. Research is no exception. While there is no quick fix to eliminating gender disparities, the EU has identified the structural changes needed in policies and programmes to increase the participation of women in research and innovation and improve their career prospects.

If you are a woman in scientific research and keen on climbing the promotion ladder, chances are your path will be long. It will also require an equal measure of confidence, commitment and courage. While there are many challenges to building a successful research career – for many women it can prove to be a real obstacle course.

Promoting equality through institutional change

The importance of institutional transformation through instruments like Gender Equality Plans (GEPs) was highlighted recently by Mariya Gabriel, the European Commissioner for Innovation, Research, Culture, Education and Youth. ‘Horizon Europe, our €95.5 billion research and innovation programme, now has new eligibility criteria,’ she said. ‘To receive EU funding, public bodies, research organisations, and higher education institutions must have a Gender Equality Plan in place.’

Gender equality has been a key priority in the European Research Area for over a decade. To remove barriers, research funding and performing organisations, including universities, were invited to implement institutional change through GEPs, and support has been provided under the EU’s research and innovation funding programmes FP7 and Horizon 2020.

GEPs are “drivers” for systemic institutional change, according to Dr Angela Wroblewski, a sociologist and senior researcher at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Vienna. This is why the European Commission’s monitoring of the implementation of the GEP requirement is key to supporting gender equality within the research sector.

As coordinator of the Horizon 2020 structural change project TARGET, her work takes an approach that goes beyond the formal adoption of a GEP. By initiating institutional change in seven gender equality innovating institutions in the Mediterranean basin, including universities and research funding organisations, the project introduced a reflexive policy (reflecting on what worked and what didn’t work) and tools for each stage of the GEP – from planning and implementation to monitoring and self-assessment.

‘When the project started in 2017, the countries where our institutions are located did not have established policies for gender equality in research and innovation,’ said Dr Wroblewski. ‘This has changed. Most importantly, our participating institutions managed to become visible as pioneers in the field of gender equality. I think this is a very important and interesting result because these pioneers may also influence the national discourse.’

The national context is important. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Any approach to institutional change needs to be tailored to fit the national context, as well as the nature, history, and mission of each organisation.

‘The challenge is to find the best solution for each institution and to have a look at the national context,’ explained Dr Wroblewski. ‘Take the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon in which female researchers “leak” out from their career path. While it is very pronounced in Central European countries like Austria and Germany, the situation in Bulgaria and Romania, for instance, is different.’

In terms of the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon, an increase in the number of women among graduates does not automatically result in an increase in the share of women among researchers or top academic staff. Many women “disappear” in the transitions from PhD student to post-doctoral fellow and to assistant professor. Others face obstacles that either slows their progression or blocks it completely. This combines with the “glass ceiling” or “sticky floor” effects.

‘This is a problem in most European countries,’ said Dr Wroblewski.

Reflecting on the work carried out through TARGET, which ended in December 2021, she said: ‘It’s very impressive what the institutions managed to achieve even in difficult contexts. For instance, the Romanian Accreditation Agency ARACIS became the first Romanian institution to adopt a gender equality plan. And the University Hassan II Casablanca became the first university in Morocco to adopt a Charter for Equality.’

‘Based on the feedback from our partner institutions, we learned it is very important to have targeted gender equality plans and to have the support to develop such plans,’ she added. ‘It is not an easy task!’

GEPs to fill the gender gaps

Entrenched gender stereotypes and gender bias are a big part of the difficulties encountered, according to Jörg Müller, a sociologist and coordinator of the ACT project.

‘I’m especially interested in how gender imbalances are made durable and continuously reproduced over time,’ he said. ‘There are many types of gender imbalances. Among the most persistent are the under-representation of women in the decision-making positions or at the highest level in academia.’

Why does it exist? While the answer is complex, the main reasons stand out. ‘The short answer is because we live in societies that have been and are still dominated by men,’ explained Müller. Gender inequality is built into the very structure of our societies. It is men who hold positions of power, decide over resources and provide the blueprint for what is valued and what is not.’

Since 2018, Müller has been investigating gender equality and institutional change. Through ACT, he has coordinated researchers from 17 institutions across the EU Member States in the creation of Communities of Practices – organic instruments of innovation in which groups of practitioners work together to solve concrete challenges. ACT supported the implementation of 8 Communities of Practice (within 144 organisations in Europe and Latin America) to promote gender equality through institutional change.

‘This is an extraordinary achievement and shows the commitment of those involved towards a more inclusive research and innovation environment,’ said Müller. ‘The Communities of Practices in many cases did allow practitioners to overcome their isolation and connect with others working in the field of gender equality. As a result, especially in Poland, many organisations made huge advances.’

This is one of the benefits of having a uniform framework to evaluate the organisational efforts. ‘This is crucial in relation to the latest advances put forward by the European Commission, namely making Gender Equality Plans an eligibility criterion to access Horizon Europe funding. This is a huge step forward.’

A next step could be the creation of a European award scheme through the CASPER project. ‘If a European award and certification system for gender equality is implemented, there will be a uniform framework to evaluate institutional efforts in terms of gender equality plans by organisations across Europe,’ explained Müller.

To increase public awareness of the importance of addressing gender equality in academic and research organisations, the European Commission is launching the “EU Award for (Academic) Gender Equality Champions” this year. Meant as a booster and to complement the requirement for higher education and research organisations applying to Horizon Europe to have in place a GEP, it will be awarded to up to four academic or research organisations.

The need to support gender equality plans

Despite some national differences, there is a common thread woven throughout all European countries: the design of successful GEPs requires both short-term and long-term commitment. This is the main goal of the SPEAR project, launched in 2019 by the University of Southern Denmark. It assists European research organisations to design their own Gender Equality Plans. By doing so, it also initiated the necessary institutional change.

‘My biggest – and happiest – takeaway from the first three years of SPEAR is how creative and effective our partners have been in applying the existing resources and knowledge to their specific contexts – and how far it is possible to go when we have access to competent guidance and time and support for qualified joint reflections,’ said Eva Sophia Myers, SPEAR coordinator.

In her role as leader of the Gender Equality Team at University of Southern Denmark, Myers knows all too well the challenges relating to gender equality, especially in the realm of scientific research. She underlines two types of challenges. The first set of challenges result from deeply embedded traditions, norms, practices, structures, systems and procedures. The second rests on competition, elitism, power and privileges.

‘Both manifest in the “real world” and in each of our minds and cognitive systems – and the two mutually enhance each other,’ she explained. ‘This means all of us favour certain directions and our everyday behaviours and decisions are largely influenced by these biases, norms and stereotypes.’

Breaking free of stereotypes hinges on our willingness to “open up” to new understandings and different perspectives. According to Myers, however, resistance is inevitable. She explained: ‘Academia is highly competitive and often the competition is about a limited pool of resources. All this gives rise to fierce power struggles and dynamics. Successful structural change brought about by gender equality approaches will inevitably challenge the status quo – including those in power positions… So, if members of academia are truly advocates of meritocracy, then working actively for inclusivity and gender equality is the only way forward!’

Rising through the ranks herself – from student assistant, research assistant, project coordinator, research administrator to inhouse organisational consultant to head of faculty administration and now head of her university’s gender equality team, Myers is an advocate of the structural change approach. ‘I find this approach to gender equality in academia to be very closely aligned with the beautiful and lofty values and ideals of academia,’ she said.

‘And in my experience, a deep integration of approaches that further inclusivity into daily practices in the universities, qualifies the efforts of university managers, PhD supervisors, teachers and researchers.’

Gender equality

The European Commission is committed to promoting gender equality in research and innovation and is taking concrete steps to address these challenges through Horizon Europe, in line with the Communication A New ERA for Research and Innovation and the new Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025. Additionally, efforts to address the underrepresentation of women in certain fields of study (such as STEM) and in decision-making positions at universities are outlined in the recent European Strategy for Universities.

Horizon Europe has set gender equality as a crosscutting principle and aims to eliminate gender inequality and intersecting socio-economic inequalities throughout research and innovation systems, including by addressing unconscious bias and systemic structural barriers.

Date: March 17, 2022

Source: Modern Diplomacy

https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2022/03/17/addressing-gender-inequalities-in-research-through-institutional-change/

Gender equality in health – still a long way to go

International Women’s Day is an opportunity to celebrate hard-won progress for women and girls. It is also a stark reminder of the remaining challenges. Women don’t have equal opportunity, representation, and quality of life – nor do they have equality in health. More than 5 million women, children and adolescents die from preventable health conditions every year.

The pandemic has highlighted persistent inequality

COVID-19 has limited women’s ability to seek healthcare. Women are less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19 than men, especially in low-income countries. For example, by the start of 2022, women made up only 35% of people fully vaccinated in Chad and 28% of those in Gabon. Women frontline workers are also more likely to have ill-fitted Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and more likely to contract COVID-19.

Yet women represent 70% of the world’s healthcare and social workers and, as such, stand at the frontline of any health emergency response. They also play a crucial role as primary caregivers for children, the sick and the elderly in their families and communities.

Disruptions in health services for women and children continue

Since the start of the pandemic, the Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents (GFF) – a multi-stakeholder partnership hosted by the World Bank that supports country-led efforts to improve the health of women, children and adolescents – has been monitoring disruptions to essential health services.

Data collected since March 2020 shows that coverage of key health interventions for women, children, and adolescents dropped up to 25% during the first year of the pandemic. In spite of improvements, disruptions persist in two thirds of countries.

Lack of access to essential health services has long-term implications to the health and well-being of women and their children. Gender disparities in health begin in the womb and carry through a person’s life, from maternal and child nutrition to access to reproductive and maternal healthcare and feminization of aging. The World Bank is committed to addressing these gender imbalances – focusing both on the immediate response to COVID-19 and on the long term.

Building up health system resilience

As Global Director for Health, Nutrition & Population and the GFF, I see three main priorities for strengthening health systems and ‘building back better’ for women and girls:

- investing in the health workforce

- strong country leadership

- and integrated quality services for better inclusion and more effective treatment

During the pandemic, we have seen tremendous country leadership and commitment, leading to important innovation. What works well in one country is not necessarily effective in another. This is why the World Bank and the GFF follow country leadership as they set priorities and identify how to achieve their objectives.

These priorities are central to the GFF Roadmap for Advancing Gender Equality and the ‘Reclaim the Gains’ campaign, launched during the pandemic, which is aiming to urgently raise $1.2 billion to support countries’ efforts to protect essential health services and rollout COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatments. The World Bank, meanwhile, continues to support reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health with IDA and IBRD lending, which surpassed $3 billion in the past five years.

Supporting health workers and integrating healthcare

As a doctor, I know that health workers don’t have an easy role, particularly in times of crisis. To give them the best possible job conditions, the World Bank and the GFF are working with partner countries to improve health workers’ training, knowledge, and tools; offer opportunities for professional development; and pay attention to the particular needs of female health workers. A motivated, skilled, and resilient workforce is the backbone of effective health systems.

Greater integration across services, training and supplies is paramount to ensure the delivery of a broad range of services. Maternal and child health, nutrition, sexual, and reproductive health and rights, in particular, must be recognized as essential care and coordinated across services and localities.

For example, in Mozambique, Rwanda and Sierra Leone, the GFF, in tandem with the World Bank, is supporting distribution of essential medications, family planning commodities and COVID-19 tools to rural and vulnerable areas, training community health workers in rolling out the COVID-19 vaccine campaign and promoting access to essential health services.

Reducing gender-based violence to improve women and children’s health

Enhancing health systems is not sufficient in itself to reduce gender disparities. Addressing social issues like gender-based violence (GBV), which exploded all over the world during lockdowns and costs the global economy around 2% of GDP yearly, is also crucial to improving the health of women and their children.

According to WHO, 16% of maternal deaths in India were attributable to domestic violence. In Ethiopia, women who experienced domestic violence were five times more likely to have babies with low-birth weight.

In Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh, the World Bank helped improve access to GBV services at health facilities for host and displaced population, resulting in a nearly four-fold increase in the use of these services.

On this International Women’s Day and beyond, we must prioritize investments in women and girls – to ensure they are afforded the opportunities for themselves, their communities, and societies. Only with equitable opportunities for all members of society will countries be able to build back stronger, reclaim the gains and sustain progress even throughout shocks and crises, such as the pandemic.

By : Juan Pablo Uribe (Global Director, Health, Nutrition & Population and the Global Financing Facility, World Bank)

Date : March 7, 2022

Source: World Bank Blogs

https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/gender-equality-health-still-long-way-go

Gender equality and women’s empowerment today for a sustainable tomorrow

As the world continues to battle and recover from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and governments look to institute policies to build back better and greener, we are at the same time affected by another global crisis – climate change – and the impact it has on women’s health, rights and equality.

Climate change is a multiplier of pre-existing forms of vulnerabilities and inequalities, including gender inequalities, often resulting in negative impacts for women and girls. Between 2010 and 2020, Asia and the Pacific accounted for three-quarters of the 122 million people that were affected by disasters. With Asia-Pacific being the most disaster-prone region in the world, we cannot ignore the disproportionate effects of climate change on women and girls.

Gender-based violence and harmful practices, including child marriage and female genital mutilation, increase among climate-affected populations. Climate-related emergencies also cause major disruptions in access to essential sexual and reproductive health services and life-saving medicines, including for maternal health care, contributing to a higher risk of maternal and newborn deaths.

Adelina, 43, from Dinagat, the Philippines, illustrates how climate change affects women as they seek maternal health care. Adelina was pregnant with her sixth child when recently Super Typhoon Odette made landfall, badly damaging the nearest medical unit and leaving her with no choice but to take a difficult two-hour boat ride to give birth in a hospital in a nearby city.

There is a critical role that all stakeholders have in ensuring that climate adaptation, and disaster preparedness, response and early recovery efforts are climate-resilient and more inclusive. This will ensure that women have access to sexual and reproductive services and information, including maternal health, family planning, and protection services. This in turn will empower women and girls to protect their rights, make choices and realize their potential, as well as strengthen climate change-affected communities’ ability to adapt.

During the Fourth World Conference held in Beijing in 1995, the global community agreed to promote an active and visible policy of mainstreaming a gender perspective into all policies and programs. More than 25 years later, we see that progress towards achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment has been slow. For this reason, UNFPA and its partners are stepping up their efforts to reverse this worrying trend and achieve universal access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health and rights for all.

As women remain on the frontlines of the pandemic and climate crisis, whether as health professionals, community leaders, educators or unpaid care providers, there is an urgent need to build the resilience of women and girls in every society at all levels to combat any crisis and ensure their access to sexual and reproductive health services and information. When floods badly affected the Rohingya refugee camps last year in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, midwife Shakila Parvin was quick to provide support on the ground in delivering sexual and reproductive health services. She also provided mental health support to families, reassuring them of the health and safety of mother and newborn after emergency deliveries.

The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development Program of Action called for making the rights of women and their reproductive health a central topic in national and international economic and political development efforts. Yet, while it is essential to achieve bodily autonomy for all people, only 55% of girls and women aged 15-49 who are married or in unions say they can make their own decisions about sexual and reproductive health and rights by deciding about healthcare, contraception and their own sexual practices.

In order to ensure a better and more sustainable future for all, it is of critical importance to accelerate transformational progress including through maternal health and family planning services, increased sexual and reproductive health-related decision-making, and by strengthening policies, organizations, and feminist and youth networks to promote and protect these issues to build resilient societies, especially in the context of climate change.

To facilitate this, UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency, is working to deliver a world where women can lead in ensuring a sustainable future.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, UNFPA calls on all governments to join its efforts and invest in achieving universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights for all, including by ensuring the meaningful participation of women and girls in climate action by shifting and sharing power with excluded groups and people – and promoting gender parity in all decision-making spaces.

By: Bjorn Andersson (Regional director, UNFPA Asia-Pacific)

Date: March 8, 2022

Source: The Jakarta Post

https://www.thejakartapost.com/opinion/2022/03/07/gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment-today-for-a-sustainable-tomorrow.html

Nigeria’s Struggle for Gender Equality Gathers Pace Amid Protests

Women’s activism in Nigeria has forced the government to take a second look at proposals that would grant women greater freedoms.

Today’s announcement by the Nigerian lower legislative chamber partially rescinding last week’s decision to throw out five key gender-equality bills is a significant victory for women’s rights advocates in the region. It is also evidence that well-coordinated political pressure by civil society organizations can produce real change.

Following reports last week that the National Assembly had rejected wholesale five bills that would have put more political power in women’s hands, scores of placard-carrying women had massed at the gates of the National Assembly Complex in Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), to peacefully protest lawmakers’ decision. The protests took place in the face of a weekslong, countrywide gas scarcity, underscoring the determination of the protesters and the resilience of civil society organizations which have championed gender equality in the country over the years. The protests then slowly spread to other states, gathering more steam today as various women’s organizations worldwide celebrate International Women’s Day.

In principle, the rejected bills sought parity for Nigerian women in a cultural context where they are effectively regarded and treated as second-class citizens. Originally proposed in 2015, the bills sought a clear path to citizenship for foreign-born husbands of Nigerian women and the right for a woman to become an indigene of her husband’s state after five years of marriage. Foreign-born wives of Nigerian men already enjoy such automatic citizenship.

More controversially, the bills proposed “the creation of one additional senatorial seat in each state of the federation and Abuja” and “two new federal constituency seats in each state and Abuja” all to be reserved for women. Individual activists and various women’s rights groups had canvassed various legislators and were quietly confident that the bills would pass.

In the end, of the eighty-eight senators who registered to vote, forty-four voted in support of the bills while forty-three voted against. There was one abstention. According to the Nigerian Constitution, an amendment requires “a two-thirds majority vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.”

Significantly, the House of Representatives’ rescission affects only the following: “a bill to expand scope of citizenship by registration, affirmative action for women in political party administration and provision for criteria to be an indigene of a state in Nigeria,” which means that the initial rejection of the more controversial proposals for an allocation of seats for women in the two legislative arms stands.

The problem the five original bills are seeking to obviate is beyond dispute. Currently, only seven out of 109 senators and twenty-two of the 360 members of the House of Representatives are women. All the governors of Nigeria’s thirty-six states are male. Yet—and to put their underrepresentation in perspective—women comprised 47 percent of registered voters during the last election in 2019.

Gender quotas have an illustrious precedent in Africa, the Rwandan Constitution being notable for reserving 30 percent of parliamentary seats for women. As a matter of fact, by 2020, women held more than 60 percent of the seats in the Rwandan parliament. For perspective, the global average for 2018 was 23.8 percent. The trend has caught on. Currently, at least thirteen African countries mandate reserved seats for women in their parliaments. The percentage of female lawmakers in the South African, Senegalese, and Ethiopian parliaments is 46, 41, and 38 percent, respectively.

On the contrary, as of February this year, Nigeria was 184 out of 187 countries in the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) global ranking of women in national parliaments. It stands to reason that women’s rights advocates in Nigeria are sick of the country’s ranking and desire parity with their counterparts in other parts of Africa.

A standard criticism of gender quotas is that they enthrone and perpetuate elite capture of power under the guise of gender equality. A related argument is that lawmaking in Nigeria is too expensive to begin with, and that adding more parliamentary seats, even if allocated for women, can only worsen the existing situation. As of 2019, Nigerian lawmakers were reportedly the second-highest paid in the world with an effective annual total compensation of $597,000. An estimated 40 percent of Nigerians currently live below the international poverty line of less than two dollars a day.

Nevertheless, even those who balk at the idea of quotas and dread the prospect of a parliamentary bloat agree that the social dice tends to be loaded against Nigerian women.

Instructively, previous iterations of the pro-equality bills made little headway because of their perceived incompatibility with religious injunction as interpreted by men. Last year, Yusuf Abubakar Yusuf, representing Taraba Central Senatorial District, refused to support the bill “until the word equality is removed. When you bring equality into it, it infringes on the Quran.” The northern part of Nigeria is predominantly Muslim.

This is not to say that only Muslim legislators were opposed to the bill. Earlier, in 2016, Senate Deputy Minority Leader Emmanuel Bwacha (Taraba South), apparently drawing on the Bible, warned women to recognize the limits to their freedom: “Every woman that has freedom must know that such freedom has limitations. She must know that there is a man that has authority over her.”

Whether Muslim or Christian, a large percentage of Nigerian men endorse this patriarchal sentiment. In 2016, during an official visit to Germany, President Muhammadu Buhari stated: “I don’t know which party my wife belongs to, but she belongs to my kitchen and my living room and the other room.”

Nor is the attitude restricted to men. According to a 2015 survey [PDF] by the British Department for International Development (DFID), in Nigeria, “Agreement with restrictive norms about gender roles in the household was almost universal, with 94 percent of men and 91 percent of women agreeing that ‘a woman’s most important role is to take care of her home and cook for the family.’” The study also noted that “Violence against women was… widely tolerated by study participants” while “Toughness, sexual performance, and income were central notions of masculinity…”

Unsurprisingly, women receive rough justice across the board and tend to bear the brunt even when they are not the immediate targets. For instance, while the average Nigerian lives in fear of casual assault by law enforcement, women are in greater danger of molestation. One reason why women featured so prominently in the EndSARS protests against police brutality in October 2020 is because more women are victims of targeted violence by law enforcement. In 2019, after police raided two Abuja night clubs and arrested sixty-five women on suspicion of prostitution, they reportedly raped those who could not afford bail. Incidents like this are regularly reported in the country’s media.

Furthermore, inter-ethnic violence and generalized banditry, as witnessed in some northwestern states, tend to leave a disproportionate impact on women. Religious violence in the northeast and kidnapping across many parts of the south tend to have a similar impact. Women constitute the majority of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Nigeria. There are frequent reports of sexual and gender-based violence, including rape and exploitation of young and pregnant women, across several IDP camps.

Women’s rights advocates like Senator Abiodun Olujimi (Ekiti South), who has nurtured the rejected bills for years, know that they still face long odds given the prevailing religio-cultural conservatism. But if there is anything to take away from the lower legislative chamber’s partial about-turn, it is that concerted and targeted pressure can yield unexpected political dividend.

More challenges lie ahead, but the momentum is with the women.

By : Ebenezer Obadare

Date: March 8, 2022

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

https://www.cfr.org/blog/nigerias-struggle-gender-equality-gathers-pace-amid-protests

Photo by: Mckenna Phillips (Unsplash)

Afghan women face increasing violence and repression under the Taliban after international spotlight fades

The Taliban reportedly captured 40 people in Mazar-e-Sharif, a medium-sized city in Afghanistan, at the end of January 2022. Taliban members then allegedly gang-raped eight of the women.

The women who survived the gang rape were subsequently killed by their families. The fact that the women had been raped violated a societal honor code called Pashtunwalli, which prohibits women from engaging in sex outside of marriage.

Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid tweeted that some of the women they arrested “remain detained because their male relatives have not yet come to escort them.”

News of the attack is circulating among various Afghan communities and some local media, according to several Afghan women’s rights activists who are part of my academic network. These colleagues cannot be named because of security concerns.

Women’s rights activists marched in Kabul on Jan. 16, 2022, asking where the women of the Mazar-e-Sharif attack have gone.

But a careful online news search in English will not reveal details about these recent kidnappings and gang rapes – a common form of aggression by the Taliban in the 1990s. No Western media has covered the attacks.

Afghanistan made Western headlines in July and August 2021, as the U.S. withdrew the last troops from the country.

Under the Taliban’s latest rule, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Afghanistan are facing “grave threats” of violence and death, according to new findings by the research and advocacy nonprofit organization Human Rights Watch.

Violence against women in Afghanistan also appears to again be worsening, according to local Afghan colleagues I know. But these reports are not eliciting international political concern.

During a major peace and conflict conference I attended with Alexia Cervello San Vicente, a masters student at Columbia University, in January 2022, participants shelved questions about Afghan women’s gender-based violence in favor of discussing trade agreements and foreign aid. Alexia assisted in the research and writing of this story.

As an expert on terrorism and violence against women, I find that the current situation for women and girls in Afghanistan is reminiscent of the Taliban’s last restrictive regime in the 1990s.

Women’s rights in Afghanistan then and today

When the Taliban first rose to power in 1996, it famously banned Afghan women from holding jobs, or even leaving home without a male guardian or chaperone.

Womens’ rights violations in Afghanistan were a major topic of public concern in the 1990s.

The general tenor of the public rhetoric at the time amplified the idea that Afghan women needed to be helped by Western countries.

Women’s rights did improve significantly after the Taliban’s fall in 2001, as women and girls were again allowed to attend school, participate in the workforce and hold positions of authority in government.

Violating a code of conduct

My previous research on women’s human rights and gender-based violence in places like Nigeria and Iraq shows that violence against women can follow a common trajectory.

Women are doubly victimized, first by gender-based violence and then by their communities, which fault women for violating patriarchal codes of conduct. These codes blame women for being sexually harassed or assaulted.

The fact that these codes target women discourages them from reporting gender-based violence and creates an atmosphere of impunity for men who brutalize women. This permissive environment has led to increased violence against women in Afghanistan over the last six months.

A similar incident to the gang rapes happened in 2014, before the Taliban returned to power – but the situation played out very differently: Former Afghan president Hamid Karzai signed death warrants for the men who gang-raped four women.

Legal retribution for the recent alleged gang rapes is unlikely, given that the Taliban have eliminated the women’s affairs office, which worked to secure women’s legal rights. They replaced it with the previously disbanded ministry of vice and virtue. This notorious government office imposed stringent restrictions on women and girls.

Afghanistan falling through the cracks

International media coverage of Afghanistan in August 2021, and shortly thereafter, focused on whether the country would lose two decades of human rights progress.

Global interest in Afghanistan and women’s rights appears to have since dissipated. One likely contributing factor is that most Western and Afghan journalists alike left Afghanistan as the Taliban gained control of the country.

But the reality for women in Afghanistan today remains unchanged. Some experts have described Afghanistan being set back 20 years.

The Taliban’s recent decree on women’s rights omitted previous promises it made to allow girls to attend school, for example.

Most secondary schools in Afghanistan remain shut, despite the Taliban’s early pledges to allow girls to attend.

A new law forbids women from undertaking solo, long-distance road trips.

Meanwhile, there are reports from the human rights nonprofit Amnesty International that the Taliban has closed women’s shelters and other social services for women experiencing abuse.

These new restrictions are making women virtual “prisoners in their own homes,” according to Human Rights Watch.

A new template for improving Afghan women’s rights

Some Afghan civil society groups have tried to encourage Muslim and traditional religious authorities to advocate on behalf of women and to give sermons about preventing gender-based violence.

The likelihood of any moderation is slim under the Haqqani network, a Sunni Islamist militant organization that is part of the Taliban.

But religious authorities in other Muslim countries could provide a template for improving women’s situation in Afghanistan.

As part of Western countries’ push to normalize relations with the Taliban, they could also establish connections between receiving foreign funding and protecting women’s peace and security.

Financial incentives could help prevent women from being stigmatized or killed. There is a historical precedent for this strategy in Muslim countries.

Women were specifically targeted when Pakistan invaded Bangladesh in 1971. An estimated 200,000 to 400,000 women were raped by the Pakistani military and Razakar, a Pakistani military group, in a systematic fashion.

The newly formed Bangladeshi government then offered financial incentives for men to marry the victimized women, reducing the stigma around their assaults.

By: Mia Bloom (Professor and Fellow at Evidence Based Cyber Security Program, Georgia State University)

Date: February 4, 2022

Source: The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/afghan-women-face-increasing-violence-and-repression-under-the-taliban-after-international-spotlight-fades-176008

The Intellectual Roots Of Current Knowledge On Racism And Health: Relevance To Policy And The National Equity Discourse

Abstract

Research related to racism and health has evolved in recent decades, with a growing appreciation of the centrality of the social determinants of health, life-course approaches and structural racism, and other upstream factors as drivers of health inequities. Examining how race, class, and structural racism relate to each other and combine over the life course to affect health can facilitate a clearer understanding of the determinants of health. Yet there is ongoing discomfort in many public health and medical circles about research on racism, including opposition to the use of racial terminology. Similarly, most major national reports on racial and ethnic inequities in health have given limited attention to the role of racism. We conclude that there is a need to acknowledge the central role of racism in the national discourse on racial inequities in health, and paradigmatic shifts are needed to inform equity-driven policy and practice innovations that would tackle the roots of the problem of racism and dismantle health inequities.

There is a current wave of increasing scientific interest in the presence and persistence of racism in contemporary societies, with health scientists paying increased attention to the measurement and conceptualization of racism as part of a concerted effort to understand how racism can adversely affect health and to identify the optimal strategies for mitigating and eliminating its pathogenic effects. Use of the term racism in research is relatively recent, and we have seen a bubbling up of a new lexicon around racism and its manifestations. While acknowledgment of racism as a determinant of health dates back at least to the nineteenth century, it was an unwelcomed idea because it was at odds with the then dominant scientific paradigm. Traditional paradigms of science that study group differences in health have historically privileged risk factors measured at the individual level that capture biological, psychological, behavioral, or other exposures that can trigger adverse changes in health status. In the case of racial and ethnic inequities, these categories were viewed as capturing biological distinctiveness in human populations, with any observed racial disparities viewed as reflecting either innate biological differences or deeply embedded differences in values, habits, and culture.

The purpose of this article is to provide a brief but cogent and chronological rendering of the alternative scholarly efforts of researchers that were foundational to the emergence of paradigmatic shifts and new constructions of knowledge. These scholarly efforts place greater emphasis on the ways in which the health of populations is deeply affected by larger institutional and policy contexts. We describe the growing attention, over time, to the centrality of social determinants, with an increasing recognition that structural racism is a fundamental but neglected upstream driver of health inequities.3 Relatedly, there has been growing appreciation of the intersections of race, socioeconomic status, and structural racism. We also provide an overview of the contested domain of research on racism, including opposition to the use of racial terminology and efforts to dilute the evidence linking racism to health. We review major scientific reports on racial and ethnic inequities, giving attention to the explanations provided and the extent to which racism is named as a determinant of racial disparities in health. We argue that the influx of racial and ethnic scholars in institutions of higher learning in the 1980s and the simultaneous attention of the US federal government to the existence of large disparities in health opened new avenues of thinking about the intersections of race, ethnicity, class, and health. Finally, we describe the critical need for paradigmatic shifts that incorporate racism as a driver of inequities and that recognize that dismantling racism is an indispensable component of policies and interventions to achieve racial equity in health.

By: Ruth Enid Zambrana ([email protected]), University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland.

David R. Williams, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts

Date: February 2022

Source: Health Affairs Vol. 41 No. 2

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01439

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01439

Book Review: Aid Imperium: United States Foreign Policy and Human Rights in Post-Cold War Southeast Asia by Salvador Santino F. Regilme Jr.

In Aid Imperium: United States Foreign Policy and Human Rights in Post-Cold War Southeast Asia, Salvador Santino F. Regilme Jr. explores how US foreign strategic support has impacted on human rights abuses in Southeast Asia, focusing on the Philippines and Thailand. This is a timely and thought-provoking read for scholars researching human rights, as well as readers interested in learning more about US foreign policy in Southeast Asia since the end of the Cold War, writes Kai Chen.

Aid Imperium: United States Foreign Policy and Human Rights in Post-Cold War Southeast Asia. Salvador Santino F. Regilme Jr. University of Michigan Press. 2021.